- Home

- G. Roy McRae

The Passing of Mr Quinn Page 14

The Passing of Mr Quinn Read online

Page 14

His mood became queerly fatalistic, and aloud he recited a quaint and entirely melancholy translation from the Chinese of Sao-Nan, whose poems are filled with ineffable sadness:

‘The moon floats to the bosom of the sky,

And rests there like a lover;

The evening wind passes over the lake,

Touches and passes,

Kissing the happy, shivering waters.

‘How serene the joy

When things that are made for each other

Meet and are joined.

But, ah—

How rarely they meet and are joined,

The things that are made for each other.’

He laughed suddenly, a little croakily. He was getting morbid. He strode on, a lithe, handsome figure of a man—such a figure, indeed, as might have come from the pages of a romance. And it was a wild and romantic adventure enough, spiced with an indiscretion and recklessness utterly alien to him, that Doctor Alec Portal was to indulge in that night.

He came at last to the walls of the convent, and they were high and grim walls, that cut out any sight of the grounds or the convent itself. There was more than a vague stirring of uneasiness in Doctor Alec Portal’s heart as he circumnavigated them—until at last he came to the iron gateway.

He heard the faint and distant sound of a bell tolling, and it increased his uneasiness.

To think that Eleanor was behind those walls, a prisoner! Virtually a prisoner, for she belonged to the world and to him. She was never made for a nunnery.

Inside the gateway he saw a tiny little house, like a lodge, from which a light glimmered faintly. Also there was an iron bell-knob at the gateway which, he reasoned, connected with the lodge. Coming to a sudden resolution he pulled it, and the bell’s clanging within the lodge sounded preternaturally loud and harsh to him.

After what seemed an age, a stately nun appeared and came to the iron bars of the gate. In a low tone Alec Portal stated the purpose of his visit.

‘You wish to see her!’ the Sister repeated blankly; and then, recovering from her surprise and gathering authority: ‘But that is impossible. Quite impossible. She cannot see any visitors.’

Alec was overcome by a sense of futility.

‘Why?’ he asked desperately. ‘Please tell me why.’ In despair and dread he added: ‘Don’t say it is too late!’

The nun looked at him mutely through the bars of the gate, and at his obvious distress, compassion and sympathy fleeted across her face. She seemed to weigh her speech.

‘Sir, you had better go your way,’ she said at last, kindly enough. ‘I do not know the purpose of your visit, but we can let nothing disturb our dear sister now.’

She turned away and disappeared, leaving Alec as if he had been struck a blow.

Perforce, he too moved away from the gateway. Though he was unconscious of it, the tiny beads of sweat stood on his brow, and his soul was pervaded by an anguish of impatience and trepidation. He was confident that something was happening beyond these convent walls—something that was inimical to his love and his hopes of making Eleanor his wife.

It burst upon him with inspiration. The bonds were being forged tonight to fetter her and hold her from him for ever. Even now, it might be, she was taking her vows!

The thought goaded him. It was said of Doctor Alec Portal amongst the medical profession that he was ever ready to rise to desperate expedients, and now he sustained the character that had been given him. He saw two iron staples in the wall, one above the other, such as are used to hold up ivy, and in a trice he was grappling with the brickwork, climbing the ten-feet wall like a cat.

Breathless and a little dishevelled, he reached the top, cutting his hands on the broken and jagged glass that was cemented along the summit. He essayed the drop on the other side, and landed with a thud that jarred every nerve in his body.

Then he was running through the grounds, wildly, erratically, like a man pursued. His guiding star must have directed him through the maze of carefully tended paths, for he very shortly came in sight of the convent itself … and the chapel, its stained glass windows flowing with coloured light, while from within came the soft and awesome strains of the organ.

Alec Portal stopped in the grounds, breathing hard. The sight of this tiny place of worship arrested him a moment, and he swayed in his purpose. Then fear placed its icy clutch on his heart again—fear that he might already have lost her, and he jerked forward towards the chapel.

Within, the strains of the organ were dying to diminuendo. A silence fell upon the strained ears of the man, silence fraught with dread for him. His hands fell on the heavy iron ring of the door, and he turned it.

He burst in. A moment he stood there, scarcely breathing, his eyes dilated as he took in the scene. The solemn awe of it caused his heart to beat as if with hammer strokes. The pews on either side, lined with silent, immobile nuns, their heads bent in prayer; the long aisle richly carpeted; and—Eleanor herself, all in pure white, and looking like a saint as she knelt before the effigy of the Virgin Mary.

‘Eleanor!’ he called, his voice like a sob of anguish.

The girl kneeling before the altar turned and sprang up, swaying like a lily. For a moment she stared across the empty space at the dark, handsome, reckless face, and then slowly a glorious smile dawned on her tremulous lips.

‘Oh, Alec!’ she said in a low, rapt voice that yet sounded clearly in that profound silence. ‘Alec—my dear! I thought you were not coming. I thought my heart was broken!’

He came to her swiftly then, down the aisle, and with a little gasp she stared at him, and about her, realising the sacrilege of his intrusion upon the scene. But Alec, deeply and fervently religious himself, did not look upon it in this light. He was a man in the sight of God, and to him it seemed a beautiful thing that this girl, to him the most wonderful of all God’s creatures, should be given into his care in such a place.

He put his arms about her, but she was trembling violently and her childish face was pitiful.

‘Alec—hold me,’ she whispered. ‘I—here is the Mother Superior.’

The Reverend Mother Superior came down the steps of the altar with stately tread, but there was a wistful, loving smile in her eyes, and faintly upon her lips. She held both her hands out almost as if she would give them her blessing.

‘You must go from this place, my children,’ she said in low, sweet tones. ‘I understand. I should be doing wrong in His sight if I endeavoured to part true love. I will allow you half an hour in the gardens in which to talk and make up your minds. Then the man must go. Eleanor, you will try to weigh in the scales against your love for this man the ideals to which you have already resolved to consecrate your life.’

So they went from the little chapel together, hand in hand, and rather like children they went along the narrow, winding paths … until the velvety night swallowed them up. Then he caught her and looked deep into her eyes. It seemed that the question he silently asked her was answered, for he drew her closer, and the eyes that gazed into hers were filled with adoration, humility and gladness.

‘Eleanor—oh, Eleanor!’ he whispered.

She was shaking, feeling her senses swooning. The translucent light of the slim crescent moon touched her face, crushed against his shoulder; and suddenly something wild and burning, like running fire, flamed through Eleanor, and she put up her little hands to bring down his face to her own.

She gasped at the touch of his lips; it became fierce, hard, relentless pressure, and he strained her quivering figure to his.

The ecstasy of that long, long kiss held Eleanor motionless, enraptured. It was as though he slowly drew her very soul from her. Weak and trembling, and with closed eyes, she lay in his arms, her hands at his heart, and in that moment she surrendered.

Whatever pain and suffering might come to her through this she could bear. She was his—his to love and worship.

Then suddenly she realised that he had relaxed his fierce grip

, that he was looking down at her with a world of tenderness in his eyes, humble and contrite.

‘Eleanor! Is it so?’ he asked huskily. ‘Do you really come to me of your own free will?’

‘My love,’ she answered, with almost a sob. ‘Look at me! Am I not in your arms? My heart!… feel it … how it throbs for you! I come to you gladly—joyfully. Why else?’

He caught her to him again. ‘My little girl! My little girl!’ he said yearningly. ‘I want you. I love you so.’

He kissed her again and again, while she lay palpitating in his arms; her hair, her cheeks, her neck and her mouth he covered with kisses; he held her and kissed her and touched her as he would have touched a beautiful flower.

‘Oh, my dear—how beautiful you are!’ he whispered huskily. ‘I burn for you, when I should kneel at your feet and be glad to live even in the same world that holds you. How queer my love, dear! I feel you to be unattainable—pure, a thing not to be touched. Yet I want to hold you—closer and yet closer.’

She did not answer him in words; with a little smile that seemed to quiver on her lips, she took his head between her hands. With a little exclamation he drew her to him again, so that her breast heaved against his and their hearts beat to the same mad tune, while he took her lips.

She placed a hand on his shoulder at last and smiled at him with a queer sadness in her beautiful eyes. ‘My lover!’ she murmured with infinite compassion. ‘You still love me—and believe. In spite of all that has happened?… my name dragged through the mire! Oh, Alex, I was made for tragedy … I have a feeling that something awful may happen yet … that nothing but sorrow and trouble can come from our love.’

He stared at her, his face dark and earnest.

‘Eleanor, we were made for each other; made for love and happiness,’ he said. ‘There are images in my mind of you; you as a schoolgirl with a pigtail and long legs; you as a sweet maid with the woman in you still slumbering, with only a shy smile and no word for yourself; you as you are now—glorious, divine. And always I’ve been near, and I’ve been loving you, Eleanor. I don’t know when I found it out, but I’ve been loving you for years. Now, if this is so, how can anything happen, darling—how can it?’

She clung to him, her little face dewed with tears.

‘Alec, dear, dear boy,’ she said huskily, ‘I shall try to believe that … oh, it is silly to think otherwise. Yet I would not hurt you now … I would not have you hurt, heart of mine.’

He could not understand. But he was not even vaguely disturbed, for he was so gloriously happy. His arms were around her, and the night gently held the sound of their murmuring voices.

That precious half-hour sped all too quickly. The voice of the Mother Superior was heard at length calling Eleanor, and she parted from her lover with the promise that Alec should see her again with the morning sunshine …

Late that night Eleanor knelt in the private room of the Reverend Mother Superior, and poured out her heart to her as she had done almost two years before. The nun listened wistfully and sadly and stroked the girl’s pale-gold hair. It had been one of her most cherished wishes that Eleanor should join the little band of Sisters in the convent, but now it was being doomed out of the girl’s own mouth as she knelt at her knee.

‘I want him so much, Mother,’ she whispered breathlessly. ‘Oh, there must be glory, and no shame in saying it … I want him!’

The Reverend Mother smiled with tears suspiciously near her eyes. It has ever been the way of youth, to take what it wants. And certainly love and life seemed full of promise for Eleanor Appleby now. The Reverend Mother asked, who was she to hold them apart?

Thus in the silent watches of the night it was settled that Eleanor Appleby should leave the convent almost at once and marry Alec Portal.

He was waiting for her outside the convent gates with the early morning sunshine, as he had said. An hour he waited, growing ever more impatient with a lover’s eagerness, whilst the dew on flower and fern all round became transformed into the rising mist that gives promise of a glorious day.

At last she came down the garden path, all in delicious white, with the Mother Superior at her side.

His heart thumped painfully at the sight of her.

He wanted to take this child-woman and lift her high in the sunlight, to look at her, and then to lower her in his arms, until the warm little face and the intoxicating lips were near his own.

But now she had come near, with the nun sympathetic but grave behind her.

‘Alec,’ she began breathlessly, ‘there were several things we forgot to talk about, to arrange, last night. I—I haven’t told you that I have no money, except a tiny bit that my mother left me. I—the other, I deeded to his relatives,’ she faltered.

‘That’s fine,’ he said eagerly. ‘I have tons, and to spare. You must come with me, and at once.’

‘Oh, I can’t,’ she faltered. ‘It—there must be arrangements. I—it is all so quick.’

‘I have arranged everything,’ he said with a lover’s masterfulness. ‘I have wired to my mother, dear, and she will arrive in Paris this evening, to care for you—until we can be married. I am arranging for a special licence, and then—my dear, our honeymoon at last!’

What could she do, or say, to deter this whirlwind lover? She had a hint of the ruthless masterfulness of him now, and secretly she adored it. The Mother Superior smiled and shook her head, but Alec was not to be gainsaid. It lived with Eleanor ever afterwards, that eager hot-headed discussion of their plans. Alec was like a spoilt boy who must have his way; and have his way he did in the end. It was arranged that he should call for Eleanor late that afternoon and take her to Paris, where his mother would be waiting to meet them.

And when the sun was laying its drugget of crimson from sky rim to rim, he came in a big Lagonda car, profusely decorated with flowers, as if, indeed, it were designed for their wedding journey. Alec alighted, looking like a big, overgrown boy, and the gates of the convent opened to usher out Eleanor with the nun at her side.

The Mother Superior smiled, first at the man, and then at Eleanor, and her eyes shone with the blinding light of a great love. Almost timidly she held out her arms to the girl she had loved as a daughter, and Eleanor bit her white lips, and then with a little anguished cry she went into the Mother Superior’s arms for the last time.

The Reverend Mother, Teresa, raised her eyes and seemed to address Alec more than the girl.

‘Children, you will be happy?’ she said with weak earnestness. ‘You will be happy together, won’t you? I do hope—it has been my fondest wish always that—’

Her voice trailed off. Eleanor remembered little more of that incident, save that with blurred eyes that saw nothing of the evening’s beauty she was helped into the car, and Alec was by her side, driving.

Paradise awaited them.

And paradise it proved to be. The hours, the next few days themselves, passed in an almost unbelievable whirl of happiness. The meeting with Alec’s mother, who seemed very happy and contented with her son’s choice; the sights and gaiety and luxury of Paris; the restaurants, and the Paris streets with their lights winking and spinning, all dazed the girl so long inured to the monotonous quiet of the convent. The shops yielded her a cascade of beautiful things; for now feverish preparations were being made for their wedding.

It all seemed like a happy dream to Eleanor, from which there must come a rude awakening. Surely never a couple so gloriously happy as they! On her wedding morn, Eleanor awoke to find herself softly repeating his name. The sun streamed through the window of her pink and white bedroom, and seemed to give her its blessing and promise of future happiness.

The wedding of maid to man can be a very beautiful thing. And so it was in the case of Alec and Eleanor Portal. The little Anglican church in the heart of Paris was smothered in flowers and the fruits of the harvest. All the friends of the couple seemed to have flocked to the church to offer their good wishes and smile upon those two who had

loved so dearly and been so long parted. Never, it seemed, had the strains of the Wedding March sounded so grand and inspiring as when Alec, tall and smiling and most unbelievably boyish, led his white bride down the aisle.

Sunshine and flowers, youth and happiness! They are the real intoxicants of life. Whirled away in the car after her marriage, Eleanor continued to live in a glorious dream, with only the fear of awakening to mar it. Blue skies, lakes; Rome—the Bay of Naples by moonlight—she drank it all in, her heart singing a wild song of happiness because he was by her side. He was such a tender lover—so good—so noble! Sometimes she was frightened by the bewildering joy of this honeymoon of theirs. It all seemed too good to be true. Could such happiness last?

They spent the last two weeks of it at Mentone, that Mecca of the carefree and gay. At nights they danced together in the hotel ballroom that looked on to the sea, and the fairy lights seemed like living jewels … And the people smiled as they watched them, for they were obviously so deeply in love.

They had been at Mentone almost two weeks when Alec first spoke of returning home. It was this that Eleanor dreaded. They had not spoken about it thus far, but then there had been so much for them to say to one another that the mundane things of life—work and reality—had been pushed into the background.

But Eleanor had known that it had to come. In her secret heart she feared and dreaded the return to the scene of the tragedy that had marred her life. She would not let Alec see that, however. She knew that all his work—his life, lay in Royston, and that they must go back.

At Mentone, Alec began to receive letters from England. He was getting in touch again.

He would read them after breakfast as they sat on the terrace of their hotel, that overlooked the wondrous blue sea. Eleanor would see the little pucker gather between her husband’s eyes; he would smile, and then frown; many times he shot a sharp look over towards her, but Eleanor, with heart beating fast for some unaccountable reason, was constrained to keep her eyes downcast, unable to meet his gaze.

But she knew of what he was thinking. Work—his patients. She told herself that she was wicked not to want to go with him, to be by his side; yet she dreaded the village gossip; she dreaded the thought of the big house that bore the red lamp of Doctor Alec Portal. It was stiff and ugly, and it was right in the heart of Royston …

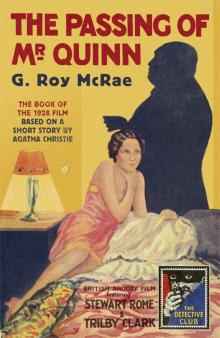

The Passing of Mr Quinn

The Passing of Mr Quinn