- Home

- G. Roy McRae

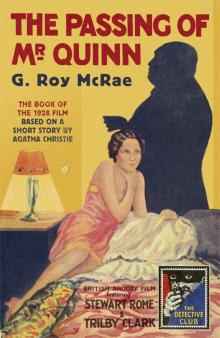

The Passing of Mr Quinn Page 13

The Passing of Mr Quinn Read online

Page 13

She could just make out a shadowy form—the form of a woman. For a moment there was a tense silence, and then distinctly she heard the sound of a sob.

‘Reverend Mother! Oh, please, let me in.’

The Mother Superior started. She knew that voice. It was the voice of Eleanor Appleby, the girl who a few moments before had been in her thoughts.

‘Just a moment,’ she said quietly. ‘I will come round and unlock the door.’

Hastily she went round to the huge, iron-barred oaken door of the convent, and even while she unlocked it she wondered uneasily at the strange despair that had sounded in the girl’s voice.

The door swung open, and Eleanor Appleby came hastily into the passage. The girl’s weary, despairing face, the tear-stains under her eyes, and even her mud-stained shoes, all indicated to the Reverend Mother the condition of her mind.

‘You look worn out,’ said the Mother Superior gently. ‘Come into my room.’

In silence they made their way to the sombre, candle-lit room that was the Mother Superior’s private apartment; and in silence the Reverend Mother sat down.

What she expected happened. The girl, with a sudden despairing gesture, sank down at the nun’s side and buried her face in her lap, giving way to a violent fit of sobbing.

The Reverend Mother softly stroked her fair hair, and looked sadly down at the girl’s shapely head. So the world treats those who are beautiful and good and unable to fight against malignant fate! It was useless to say anything while she was in this pent-up condition. The Mother Superior waited until the dry, choking sobs that seemed to rack the girl’s whole frame gave place to the relief of tears. She became silent at length, and seemed to grow calmer. Then, and then only, did the nun speak.

‘Tell me all about it, dear.’

The girl’s pain-stricken eyes in the almost transparent little face were turned on the nun’s calm, serene countenance, and for a moment she fought for control to speak.

‘Mother,’ she whispered huskily, ‘I have done wrong. A terrible wrong. Heaven help me—what shall I do?’

She broke off pitifully.

‘What do you mean, dear?’ The nun asked the question a little sharply. The little imps of fear commenced to play on her nerves as she waited for the answer. It couldn’t be— It was impossible to think of any serious wrong in connection with this sweet child!

‘I must tell someone,’ the girl whispered shamedly. ‘Mother, I must confess. It’s about me—about—’

She stopped, her face white as death as she lifted it piteously. But somehow she seemed to gain courage from the saintly eyes that looked with infinite compassion down upon her, and in very low and broken tones she made her confession there to the Reverend Mother Superior in the quiet of the candle-lit room.

The nun sat in shocked silence, while the girl talked haltingly, in broken tones. Then at last it was over, and a silence fell. Eleanor buried her face again, while the nun stared before her with eyes that saw nothing. She understood now, and she knew the terrible tragedy that had stamped itself on this girl’s mind.

And as the Reverend Mother sat there, she came to her resolution. Weak and sinning though this girl was, she would take her into her fold. She should take the veil, become a nun. To the world outside her confession was as if written in a book that is sealed for evermore. And Eleanor! She had cast her eyes for the last time on the world outside the convent gates.

That was if she wished it; and she had expressed that wish. The Mother Superior had no reason to doubt from her present attitude that she had altered it.

There was a painful pause. Eleanor was staring in front of her as though she saw everything again. And she was trembling violently now.

‘Mother, Mother—what shall I do? Speak to me! Say something! Oh, am I so vile in your sight?’

Still the Mother Superior said no word, and Eleanor gradually grew rigid as she knelt there at her knee. She had poured out her confession. At last to one other person she had entrusted the secret that had been so long locked in her heart, that had seemed to be killing her. This silent nun knew of the part she had played in the dreadful happenings of that night.

And she condemned …? Righteously she condemned. Yet the Great Teacher has told us that there is no sin that cannot be expiated by remorse and suffering and sorrow. In such coin had Eleanor paid. She would go on paying until the bitter end.

Now her heart was racked with almost intolerable grief and wild, tumultuous pain. She had staked so much on this moment when she might ease the burden of her mind by confession. During the whole of the trial the thought of the quiet convent and the saintly Mother Superior had helped her to bear up, and she had struggled always with this haven in sight.

All along she had told herself she must tell someone—she must! And there was no one else she could tell her secret save the nun. She had hoped for surcease from the strain of it all. For she was one poor sinner who could not support the burden she had to bear … And now this—this frozen silence! It was more terrifying than death.

A little gasp came from the suffering woman’s lips; still the Mother Superior did not speak.

Eleanor rose to her feet quietly, looking like a wraith. Her face was deathly white, her great brown eyes like pools of fire. There was a vacant intensity in her gaze that instantly frightened the Mother Superior, who roused herself; she had been absorbed in queer, dreadful thoughts.

‘I’m going,’ Eleanor said; and her usually clear, musical voice had become droning. ‘I’m going to tell the police. I can’t stand it any longer. It’s weighing on my conscience.’

She turned away to the door almost like a somnambulist. Her brown eyes in her deathly white little face were blazing with a strange light.

The Mother Superior rose, and her swishing robes spoke of unusually quick movement as she followed the girl. Almost at the door she caught the slim figure in her arms.

‘Eleanor,’ she cried in poignant distress, ‘would you leave me now? Oh, my poor, poor child—of what are you thinking? What do you contemplate?’

The Mother Superior’s anguished, loving tones seemed to move the girl (who had appeared to be almost in a state of trance). Slowly she turned her beautiful, staring eyes on the nun.

‘Reverend Mother,’ she said, with a heart-tearing sound between a gasp and a sob in her voice, ‘I seemed to see a dark pool just then, and there was a spirit hovering over it that seemed to beckon, inviting me, It seemed to tell me that in the pool’s dark bosom was my only refuge. I have got to make amends. And—heaven help me!—I cannot go to the police!’

‘Why not?’ the nun involuntarily cried.

‘Because,’ the girl cried in a voice that rang like a knell of despair through the sombre room, ‘they won’t take me. They have told me that I am free—free for all time. They will not try a person twice for murder in England. Oh, heaven, how shall I make amends? Only by the pool … the spirit of the pool is calling me.’

‘Nay,’ whispered the nun, with tears in her eyes as she clasped the girl closer. ‘Nay, my child; it is another voice that calls you. He has said “Come unto me all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.” Eleanor, it is another voice that calls you—the voice of the Church.’

She looked at the nun, a great question leaping in her brown eyes. And the Mother Superior tried tremulously to smile. Then suddenly she had the whole weight of the girl in her arms. Eleanor’s eyelashes had fluttered down, and with softly expended breath she swooned.

The nun half carried her to a chair and applied restoratives. But as she bent over the girl, gently touching her temples with cool fingers, the Reverend Mother Superior’s brain held a whirl of chaotic thoughts.

She looked so innocent—so peaceful and pure, sleeping in oblivion there. And yet—

The nun shuddered and made a valiant effort to dismiss the whole matter from her mind. She had heard of people in a state of trance doing things, committing deeds for which they were not responsible. And afterw

ards their minds were blank. They had forgotten—or never remembered—those particular actions.

One thing was certain. Eleanor Appleby had been more sinned against than sinning, and if time could heal, if rest and quiet could ease her mind and make her forget the dread past, then the Mother Superior was determined that within the cloisters of St Augustine’s Convent Eleanor Appleby’s spirit should be healed.

And so it came about. Following her swoon, Eleanor was ill and delirious for many days, but the gentle nursing and care of the nuns pulled her round. Soon her slim figure in simple black might have been seen wandering in the grounds of the convent. Autumn passed to black winter—which became a white winter in January; and the Sisters of Mercy were seen more outside the convent, carrying supplies of food and fuel through the snow to the poor of the village. At long last bleak winter gave place to spring with all its sweet, shy promise. But spite the daffodils and the primroses, the chirrup of birds and the glint of green buds on the trees—despite the seductive soft whispering of the wind, Eleanor did not hear the call of the outer world.

She tended the garden with the nuns, and gave more and more time to her private devotions. Serenity of mind had come to her, and she was preparing to take the veil.

Perhaps she stifled a sigh at the scent of the May blossoms, and at the fluttering freedom of the butterflies. With summer the convent garden became a riot of bloom, and of times a fancy came to her of another such garden as this where once a mere boy in knickerbockers had chased a girl in a gingham frock, and screaming laughter had echoed through the rose bowers and rookeries.

Hide-and-seek in an old-world garden! It had been one of her earliest memories. Youth—joyous laughter—freedom! Eleanor felt very old and weary as she looked around her and saw the starched white linen and black robes of the nuns through a curtain of tall hollyhocks.

But she was ready. She was nearing the end of her novitiate stage now, and soon would be prepared to take the vows. Ten—eleven—twelve months had gone past. More. She had not counted them after a time.

She thought of Alec Portal, and immediately dismissed him from her mind again as she had schooled herself to do. He had not come; and besides she did not want him to. She had resigned herself to this quiet secluded life in a convent garden where nothing ever seemed to happen and time itself stood still.

The heat was oppressive today …

She looked up at the sun, a fierce brazen ball, and then her gaze wandered down to the ground and fixed itself on a little troop of ants scurrying in and out of their hill. Yes; even here in a convent garden the world and Nature were busy. Things lived.

Only she had a heart that was dead within her …!

She turned her steps towards her cell with something like a sob in her throat.

CHAPTER VIII

TIME slips past remorselessly. When we are very young each day seems an æon of time; for our eyes are strained to glimpse some rosy future. Then the sands of time slip out one by one. When we are older we turn our backs, and work—and we are astonished at the diminishing in the glass when we pause to look. When we are very old, then everything gallops and rushes past us, and, dazed by the mighty problem of life, we wait for everything to become quiet.

Doctor Alec Portal plunged into work. Every illusion had been stripped from before his eyes, and he saw the future as a thing that was smashed. He worked unceasingly day and night. His practice grew larger and more prosperous until he was obliged to employ two doctors as locum tenens. The staffs of two great London hospitals that knew him as a colleague watched his progress and predicted a wonderful future for him.

But Alec Portal saw no future for himself. He dared not look into the future—alone.

Work had become a distraction and an anodyne. He worked to still a gnawing pain and hunger. Perhaps he worked so hard also to forget the one letter he had received from Eleanor, and which lay unopened and unread in his desk.

He had received that letter long after the reports had reached him of the notorious Mrs Appleby’s activities on the Continent. She was a cabaret dancer in Vienna, he was told. She had a fatal attraction for men, this remarkably beautiful fair-haired woman, who, it was openly stated, had poisoned her husband. There had been many subsequent scandals with which her name was linked.

‘Midst all these activities of hers she had found time to send him one letter from France …

It is a regrettable fact that human nature is ever more prone to suspicion than to faith. Alec had helped her so much. He had stood by her side and fought the battle with her during the trial. And now—he tried to banish those sweet and tender memories of her; tried not to think of her. If he did, it was certain that suspicion would insidiously creep into his mind and torture him.

Had he been wrong? Given his love and faith to one whom he thought pure and good, and who was in reality … a scheming wanton?

He fiercely repudiated the thought. It hurt his self-respect to think that he had been deceived by a beautiful face—those glorious eyes. So complex is the nature of man that he almost forgave what he readily accepted as her subsequent conduct; the wild plunge into gay and riotous living. That was a reaction to the tragic circumstances of her life, he thought.

He should have been by her side to help her—care for her—love her. Things would have been different then. He should have insisted on it.

But that she had deceived him right from the start! Never. It was impossible.

So he tortured himself. And he would not open the letter that had come for him, though it tempted him daily and hourly. He plunged into work to feed his ego, which was the greatest part of him, and so he became, in less than two years, what the world would describe as a successful man.

It was one evening when he was working late in his surgery that Chief Inspector Brent called. Though they still lived as neighbours in the village of Royston, the event of this visit was entirely unprecedented. Indeed, the two men had not seen one another since the trial, and Doctor Portal’s eyes gleamed under his fair drawn brows as the Yard man came up the steps and through the little glass house apartment where medicines were placed for callers. He turned the handle of the door and came in like a very tired man to familiar surroundings.

He dropped into a chair with his hat in his hands while Doctor Portal stared an inquiry.

‘Good-evening, doctor,’ he said, with that heaviness that never left him. And after a pause: ‘I’m all wrong again, doctor. This case has worried me since its inception. It was I, you remember, who wrote to you to inform you that Mrs Appleby was performing in a cabaret in Vienna and sent you those foreign newspaper cuttings about her. Well, it’s a hoax. A damned hoax. Another woman has been stealing her thunder, as you might say. Masquerading as her.’

‘What!’

Alec Portal was visibly galvanised. He crossed to the inspector like a striking hawk and seized him in an iron grip on both shoulders. His fair face was very fierce, and the teeth gleamed above the jutting chin.

‘Say that again, you big false alarm!’ his voice crackled.

Inspector Brent’s eyes were very weary in his heavy but clever face as he lifted them. ‘She’s in a convent in France,’ he explained listlessly, in lieu of repetition. ‘Been there for two years. I believe she’s becoming a nun. And I’ve been spreading reports about that little woman,’ he added with almost a groan. ‘God, the world owes her a lot—’

Alec Portal released him and stood as if he listened to the earth’s last tremors.

That letter! And he had never opened it. Fool—mad fool that he had been. To allow carking doubt and suspicion to enter his soul while she …

Inspector Brent rose and buttoned his overcoat. Embarrassment made his speech rather stilted and gruff, but he spoke the piece he had come to say.

‘You’d better hurry up, young man,’ he delivered himself. ‘If I was young and in your place, I wouldn’t let that little woman become a nun. I’d arrange quite a different religious ceremony. And I don’t mean may

be either.’

He drifted towards the door, and out into the night. As he walked home he sighed more than once. Inspector Brent was a bachelor, and he told himself it was much too late for love to come into his life. In this he was probably right. Besides, the position was positively absurd … So Inspector Brent did his best to quench the slumbering fires in his heart.

And Alec? No sooner had the inspector gone than he darted away. Very quickly he had that pitiful little letter in his hands, and was reading it again and again.

‘Alex dear,—I am so lonely and heartbroken … If you still want me … come …’

He kissed the letter passionately, and then with shining eyes he looked up. God, he’d go to her—aye, and take her … if it was not too late.

At that dread thought he became a whirlwind, so that he aroused the whole of his household. The doctor who was his assistant was obliged to look up the times of the boat trains for him, and his housekeeper looked on horrified while he thrust immaculate suits and shirts haphazard into a travelling case. Never before had anyone seen Doctor Alec Portal so futile in any of his endeavours, and the end of the upheaval witnessed a figure dashing down the steps of the porch into his own car, whilst the chauffeur meshed into gear preparatory to sending the big Studebaker on a sixty mile an hour rush to Southampton.

Alec Portal, however, had a long time for his own thoughts. And any gladness he knew at going to her was tempered by dread. He spent a night tossing and turning. Suppose it was too late. Suppose— Hours he spent conjuring up visions of her, and the dread conviction grew on him that he had lost her.

Comparatively, it seemed like being in heaven when at last the train delivered him at the railway station outside Caldilly. It was just such another night as that on which Eleanor had walked to the convent. The wind sighed through coppice and wood with gentle melancholy, and as the man trudged on he passed the village pond, its waters slightly ruffled, yet almost silvery under the light of the moon, which hung high above like a Chinese lantern in an immeasurable temple of silence.

The Passing of Mr Quinn

The Passing of Mr Quinn