- Home

- G. Roy McRae

The Passing of Mr Quinn Page 3

The Passing of Mr Quinn Read online

Page 3

‘Listen,’ he said evenly and grimly. ‘The rest of the world lies outside this house. The house is mine, and so is everything in it,’ he added. For a fraction of a moment he stared at her, and in his glittering eyes she read what his words but thinly disguised.

She was shuddering violently at that look of sheer, animal gloating—it made her sick with terror.

He had changed now. And the metamorphosis in him was more frightening than any she had ever known. For he became the ardent wooer.

She almost cried out when he stretched out his arms. Then he caught her to him, and she was crushed against him in a savage embrace that nearly suffocated her. Again and again she tried to cry out, to push him away from her. But his lips were seeking hers.

His arms were around her, and the touch of her soft, girlish form suddenly seemed to set him afire with the desire for possession.

‘You witch!’ he said hoarsely. ‘You can’t get away from me now. You’re mine—mine, d’you hear?’

Sick with terror she nearly fainted. A low cry broke from her lips.

‘Oh, please … please … have mercy … If you have any chivalry in you have pity on me.’

But he only laughed at her.

‘Little wife; there’s something I want. You’re going to give it to me, or else—’ He stopped, but the words had purred out of his mouth with a cold terrific deliberation that frightened her more than anything that had yet happened.

White-faced, ashen, she stood against the wall, staring at him. Professor Appleby was lighting a cigarette coolly and deliberately.

‘Go to your room,’ he said. And then after a significant pause. ‘You understand?’

She gasped. And then all at once with a low cry of anguish she turned and darted from the room like a startled fawn.

After she had gone Professor Appleby laughed—his soft, mirthless laugh, and inhaled deeply of his cigarette. He sat down at the piano and played Rubinstein’s Melody in F softly, and with the touch of a master. An animal cruelty glowed from his eyes. He felt somehow that tonight the crisis would be reached. He had goaded his wife to the last pitch of desperation; a little more and her taut nerves would snap.

He was not sure that he wanted that. He preferred to play with her a little longer as a cat does with a mouse.

At last, with a little twisted smile on his lips, he rose from the piano, and softly closed the lid.

Treading like a cat he crossed the carpet, opened the door and mounted the stairs. In her room, Eleanor heard his stealthy footsteps along the corridor, and she looked up like a startled fawn. It was he! He was coming as he had said!

Her distress was pitiful, and she was in a state of bodily as well as mental torment; so much so that she was forced to hold her hand to her heart to stay the agony of its wild beating.

The soft footsteps came nearer. A vein throbbed madly in Eleanor Appleby’s temple as she crouched back on the bed, and looked up towards the door.

Then she saw his shadow, huge and grotesque, thrown from the illuminated passage into the bedroom, lit only by its tiny reading-lamp. Professor Appleby’s face and figure became framed in the doorway. Eleanor felt her senses swooning, and a little cry escaped her.

Professor Appleby laughed softly as his eyes devoured her crouching back on the bed. The light from the passage brought into relief her gleaming white arms and throat, the oval face with its expression of childish anguish. Professor Appleby stretched out a hand from the doorway, and its shadow leapt ahead, and seemed to make with twitching fingers at his wife’s throat.

The strain of it on her overwrought nerves was too much, A little shriek left her lips.

Professor Appleby echoed it with a soft laugh.

‘Very well, my dear,’ he said from the doorway. ‘The night is young yet. I will leave you to compose yourself.’

He withdrew, and walked softly down the passage polishing his monocle. This he screwed into his eye with a portentously solemn expression. As a matter of fact, dignity became Professor Appleby very well, and he was able to face the world with a very good countenance. His lapses from dignity were, therefore, all the more shocking, and when the insane light glowed from that heavy, intellectual face it provided a nightmare sight.

He strove to fight his enemy as he descended the stairs. A nerve twitched visibly at his temple. He told himself he was a celebrated figure. The taint of insanity! How ridiculous such a suspicion was in connection with himself! Only the previous day a daily newspaper had published a two-column eulogy on his brilliant research work.

He wrestled with his demons as he descended the stairs. Then all at once he gave a real start as he saw a neat figure in black kneeling at the foot of the stairs, ostensibly brushing the carpet.

Professor Appleby smiled beneath frowning brows. It was Vera. It fed his ego to think that he had paid for the black silk stockings that so enhanced the charm of the house parlourmaid’s figure … Though he wanted nothing more to do with her now. A scowl darkened on his face as he manœuvred to step past her.

The girl—she was comely, even pretty in a coarse way—looked up at him with a haggard face and a pathetic smile on her lips.

‘Sir!’

His momentary anger was gone, and he looked at her indulgently. Indeed for a moment a lambent flame shone in his eyes. She was a trim enough figure in her rather short black frock and white lace apron. Professor Appleby, who had carried on a vulgar intrigue with this woman, and had tired of her—forbidding her, indeed, to come near him, showed a little relenting now for the first time for weeks.

‘Well,’ he asked softly; ‘what is it you want—more money?’

The girl gained courage, and smiled at him coquettishly. She began to believe that she had not lost her hold on him after all, and her visions of what she might expect enlarged correspondingly. She knew that he hated his wife, and, indeed, she had helped him in many a subtle cruelty he had practised upon Eleanor Appleby. And now, tonight that he appeared to be in softer mood, she determined to make a bold bid for him, though secretly she was more than a little afraid of him.

‘It’s something very important I’ve got to tell you,’ she said, glancing at him archly. ‘You’ve been very cruel to poor little me these last few weeks. I’ve been afraid, but—oh, you must listen to me. You must.’

Professor Appleby smiled. His glance was like a cold little searchlight playing on her. His curiosity was roused. But she appealed only to his instincts of cruelty now. He had taken his pleasure with her, and she had no longer power to quicken his flaccid interest.

‘I shall be in the study,’ he said after a long pause. ‘Your mistress will not be down again, Vera.’

She nodded dumbly, afraid once more of the sinister side to this man, and Professor Appleby, screwing in his monocle, strolled first into the drawing-room, leaving the door open for a purpose of his own.

With cat-like tread he crossed over to the grand piano, whose sides gleamed sardonically, as if the instrument also enjoyed the cruel jest he contemplated. Lighting a fresh Turkish cigarette, he sat down at the stool, and his fingers caressed the ivory keys. Genius was in his touch, and his voice had uncanny powers of gymnastics. Melody throbbed through the room as he sang and played.

‘I know not, I care not, where Eden may be,

But I know

I’m in very good

Company.’

He laughed. The old, old song had been one that Eleanor’s mother used to sing, and it always brought the tears to his wife’s eyes when she heard it. For there is a memory in a song—memory and associations and passionate longing. And from his wife’s heart with that song he knew he could wring the bitter, bitter cry: ‘Mother, if only you could come back—come back!’

But she had no one in the world. She was merely his possession to do with as he liked.

Upstairs in her room, Eleanor heard the song with its sinister mockery, and something died in her heart for ever. Her pride, her most cherished possession, was beaten to

the ground. She was frightened—frightened of being in this big house—frightened of being alone with him.

The tears were rolling down her cheeks, and she made no effort to repress them.

Then, at last, in a panic that he might come again, she climbed off the big downy bed.

Feverishly, desperately, she crossed to the telephone in her room. A silence had fallen in the drawing-room, and she knew her husband’s uncanny gift for discovering everything that went on in the house. But she must do it—she must! In a queer, fluttering voice she asked for a number. She hung up the receiver and sat still, the heart of her beating madly. Derek Capel. Queer that she should think of him now. But they had known each other since childhood, and Derek had said when she married that if ever she needed a friend …

The telephone bell rang stridently. She stared at it a moment, almost as if she expected an apparition to issue from its mouthpiece. Then with trembling hands she took the receiver again.

Derek Capel’s manservant answered the ’phone; and in answer to her low-voiced inquiry he informed her that his master was not in; he would not be back until later.

She replaced the receiver with a sense of utter, wild desolation.

Derek! He was so strong, so self-reliant. She needed someone. After a long moment she went to her writing-table, and feverishly scribbled a note to him.

‘Come round … some time tonight. Derek, you must. I’m frightened—frightened of him. I’ve got a feeling that something dreadful is going to happen tonight. My husband has—oh, I cannot tell you. He is a brute. He is not fit to live. If I had the courage I believe I would kill him myself.’

She folded up the letter in haste, and put it in an envelope and addressed it to Derek. If she hurried downstairs now she would catch the gardener, and he would take it and keep silent for a few shillings.

On tiptoe she sped down the stairs, the letter in her hand. The broad staircase turned rather abruptly to face Professor Appleby’s study door. She had expected the door to be closed as usual, but as she came round a blaze of light struck her like a blow.

It seemed to Eleanor Appleby then that her heart stopped beating.

For seated at the table with an ugly look on his white face was her husband, and kneeling at his side, pleading with him with tears in her eyes was a woman.

CHAPTER II

THE silence that had fallen a few minutes earlier in the house had been occasioned by the cessation of Professor Appleby’s playing, and his strolling into his study next door. He closed the door very carefully, and turned to find Vera, with flushed face, regarding him with an odd light of triumph in her brown eyes.

She crossed to him with a peculiar feline grace that had once attracted him, and placed her arms round his neck.

‘My dear—oh, my dear!’ she whispered. ‘I’ve wanted to see you alone—oh, so much. And you’ve kept me at arm’s length. You’ve been so cruel.’

He suffered her caresses, and his vanity was pleased by the mad heaving of her bosom against his shirt front. The girl was evidently distrait. Her eyes were unnaturally bright, and whereas, at their first wooing, she had given herself timidly, fearfully, she now sought for his caresses with wanton eagerness.

Professor Appleby did not at once repulse her: nevertheless there was a cruel glint in his eyes. He had brought her to the dust, and he was fully determined to deal the final blow.

Together they crossed to his desk, and the professor sat down, while she knelt beside him, talking to him excitedly and a little incoherently. Formerly she had been rather like the slave girl who suffers her master’s caresses in silence. But now her stress of mind—her very real need—engendered in her a new boldness.

‘You do love me a little—just a little?’ she said repeatedly. ‘Say you do. Hold me in your arms like you used to.’

Professor Appleby sat with broad, stooping shoulders, staring through his monocle, and wondering. It baffled his ingenuity to guess what she wanted from him.

He turned to her at last, and asked her point-blank.

The false gaiety dropped from her, and her hand went up instinctively to her bosom. Now that the crucial moment had come she was afraid. But she had to speak to him—she must.

‘It’s something very important, sir,’ she said, and her voice sounded like a voice in an empty cathedral. ‘If you don’t help me, I’ll—oh, it’ll be my ruin.’

Professor Appleby started.

Before he could speak the woman threw her arms around his neck and whispered something. It confirmed the professor’s suspicion, and he struggled to throw her arms from him, his face thunderous in its rage.

‘What! You dare to tell me it is I, you—you you—’ He stopped for a word. Rising to his feet he shook her off, and crossed savagely to the door. ‘Get out! Pack your things and get out, you wanton. Don’t let me see your face again.’

She faced him, and now she was a virago with flashing eyes and white-streaked face, albeit her voice was pitched low.

‘You made me what I am. You! You—no one else! Oh, yes; you pretend not to believe me. But will that doll-faced wife of yours believe? Will the world believe when they see your—’

He turned with a hiss, his hand upraised to check her, his face black as thunder.

She fell to whimpering, awed and frightened by his aspect.

After a pause Professor Appleby crossed to his chair again and slumped into it. The first thunder-struck surprise was giving way to ferocious cruelty. He’d make her suffer for it. She threw herself to her knees and clasped her arms round him, pleading, cajoling, bursting alternately into fresh sobs.

‘Won’t you—come away with me?’ she begged almost in a whisper. ‘I’ll work for you—slave for you all my life. I’ll do what that doll-faced wife of yours could never do; I’ll make you love me. It’s not money I want, it’s—’

He burst into a ferocious laugh at that, and shook her off.

‘It’s neither that you’ll get from me, my dear Vera,’ he said in his coldest tones. ‘Not a penny piece—nothing, except orders to quit at the end of the week.’

With a terrified gasp she looked at him.

And in his leering eyes she read the truth. He meant it, every word. She struggled to her feet and backed away, staring at him almost fearfully. This was the man to whom she had given herself. And he was as remorseless now in his hatred of her as he had been in his desire.

‘You—you can’t send me out with nothing,’ she whispered.

‘I can, and will,’ he said in his coldest tone. ‘You will leave at the end of the week with a week’s wages.’

‘But what shall I do?’ she gasped. ‘I can’t face the disgrace, I—’ And then suddenly rage transfigured her, and she stamped her foot.

‘You monster! You vile brute!’ she cried in low, tense tones. ‘I’d like to kill you. Oh, if only I could see you die before my eyes now—dying in agonies, I’d be satisfied. Such men as you shouldn’t be allowed to live. I—’

Her voice trailed off in a sob. There was a gathering storm in Professor Appleby’s eyes that caused her to quail a little. Then all at once he started, fancying he heard a sound in the passage, and holding up his hand to her, he crossed on tip-toe to the door.

As he peered out he fancied he heard a flurry of white disappearing up the staircase. He was not quite certain, and he tiptoed up them, but as he peered in his wife’s room he saw that she was in bed and apparently asleep.

Satisfied, he returned.

Down in his study Vera, the house parlourmaid, was glancing around her wildly. She was a little mad. All sorts of thoughts were seething in her head. She hated this man who had betrayed her—hated him with an intensity of feeling that knew no bounds. And in her veins flowed a little gipsy blood. A dangerous mixture. She was not the type of woman to suffer a wrong calmly.

Her eyes espied the medicine cabinet on the right side of the room, and she crossed to it with a rustle of her silk petticoat. There was one bottle on the highest shel

f, a little, blue-black bottle marked ‘Poison,’ and her hand went out to it quickly.

Then she started as she heard Professor Appleby’s softly returning footsteps.

When he re-entered the room, she stood at the far end of the room, near the French windows, and near the little round mahogany table that held the professor’s wine decanters and a syphon of soda. Professor Appleby had made it a habit of taking a glass of port before retiring to bed.

Vera held her small useless lace apron to her eyes, and her form was shaking with dry, pent-up sobs. But Professor Appleby was in no mood for further hysterics. He crossed to her and grasped her shoulder in a cruel grip.

‘Leave this room,’ he said in a low voice of menace. She turned with one last defiance, and there was so much deadly earnestness in her tone that it might well have warned Professor Appleby.

‘All right; I’m going,’ she said stormily. ‘I never want to see you again, you monster. But depend upon it, you’ll be sorry. You’ll be sorry!’

Professor Appleby’s lips twitched in a sneering smile as he watched her go with shaking shoulders.

He sat down at his desk again, and for some time engrossed himself in work. He was preparing an important paper to be read at a conference a week hence. But though Professor Appleby did not guess it, forces over which he had no control were shaping to engulf him that night. He was never to read that paper at the medical conference.

Though everything was quiet, save for the ticking of the grandfather clock in Professor Appleby’s study, over the house there seemed to hang a brooding threat.

At a distance of little more than five miles away the stately old pile of Capel Manor reared itself against the night sky, its windows lighted and warm with red blinds.

In the drive outside the front door stood a giant Mercedes car, its engine purring almost silently. The owner of the Manor, Derek Capel, had returned home at nearly midnight, after one of his wild and reckless rides through the countryside, but since none of the servants, least of all Derek Capel himself, knew whether he should want the car again, it was left with its engines still running and its headlamps cutting swathes of light through the trees in the drive.

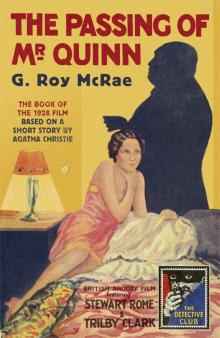

The Passing of Mr Quinn

The Passing of Mr Quinn