- Home

- G. Roy McRae

The Passing of Mr Quinn Page 11

The Passing of Mr Quinn Read online

Page 11

A moment she looked at him strangely with her large and beautiful brown eyes. It was as if she were in a state of coma, hypnotised by that suggestion. Then slowly a terribly hunted look crept into her eyes, and trembling visibly, she clutched at the rails of the witness-box, shaking her head.

‘You knew,’ counsel accused her, with a terrific venom now in his tongue and look. ‘You knew that the decanter contained poison. You had poisoned your husband, and you did not wish to poison the man you loved. Come, tell the truth.’

It was the supreme moment. She was beaten down, with all the spirit gone from her. She had passed through a frightful ordeal such as might have broken the spirit of the hardiest and caused reason to rock. Even those in the court who believed her guilty—and there were many there!—watched her in tense anxiety. But all at once, after a slight fit of shuddering, she raised her head proudly and uplifted her arms with a strange, rapt splendour in her eyes.

‘Heaven hear me,’ she cried, in a clear voice that thrilled the court, ‘I had no knowledge of any noxious or poisonous contents of the decanter. Alone in the world, reviled, wrecked for all time, without a ray of hope, I, Eleanor Appleby, deny every accusation brought against me in this cruel arraignment. I am innocent! Innocent! Thou, God, knowest! Innocent of this sin, as the angels that see thy face.’

And then, with a little choking cry, she collapsed.

Hardly able to conceal his disappointment, Sir Hugo Rattenbury intimated that he had no further questions to ask. The case was marching swiftly to its conclusion now, for counsel for the defence did not wish to examine prisoner at the bar, and an adjournment was ordered for lunch.

After the luncheon interval, David Greatorex, K.C., rose to his feet to make his final speech for the defence. It was a marvellous piece of oratory, impassioned and skilful, lasting for two hours. It can be read by the curious today who seek among the blue books of the Record Office, and even in cold print it stands as a fascinating and moving exposition of the forensic art. How much more moving was it when delivered by Mr Greatorex himself to a hushed and breathless court? His was a personality that could hold audiences spell-bound and sway emotions as the wind the full-blown corn. Those in court stared at the gaunt figure with its enveloping gown, the keen, ascetic face with the dark eyes aglow, as if at a prophet, and they listened with a tingling shiver to the voice that rang like a bugle call:

‘Gentlemen of the jury, what madness does the law perpetrate, what hideous injustice in asking you judicially to murder this innocent and pure-hearted woman? I am astounded. You have heard the facts—the dark array of facts that the prosecution have brought before you. After subjecting this young and sensitive girl to months of unspeakable agony and torture, they have arraigned her before the bar of Justice on a charge of murdering her husband—and they cannot tell you how he died!

‘It is a monstrous thing,’ went on the advocate passionately. ‘It is a blunder so frightful that it borders on as heinous a crime as that for which their victim stands arraigned. Consider it, gentlemen of the jury. An autopsy has been made on the body of the deceased by the most clever pathologists in the world, and all they can say is that there is evidence of poisoning, and that they suspect a subtle and little known poison that will give evidence of its presence in the organs after a period of time has elapsed. For shame! Upon that risky prognostication to hustle a young and innocent life beyond the Great Divide!

‘What else is outstanding amongst this dark array of facts that confronts you, gentlemen of the jury? The Crown have pinned all their faith upon the accused’s breaking of the port decanter. They have analysed the pool on the floor and discovered no poison in it. You have had evidence to show that there were two glasses in the study stained with port after the professor’s death, and the ether person, Mr Derek Capel, who drank from one of the glasses, is not dead. Do you for one moment give credence to this ridiculous theory that the professor’s port had been poisoned?’

Counsel for the defence went on to argue most eloquently that the professor’s glass of port, already poured out, might have been poisoned by accused rather than the decanter. What then was the object of smashing the decanter?

He dealt at great length with Doctor Alec Portal’s evidence, adducing it as eminently reliable. The deceased was a man of brilliant gifts, who dealt in vivisection, anthropology and other sciences that were essentially of a cruel nature. Whether his studies preyed on his mind or not, he was certainly a victim of incipient insanity. Might he not have taken his own life? He was versed in poisons. He hated his wife, and with the cunning of an insane person, he might have planned this fearful aftermath of his death—the trial of his wife for murder.

David Greatorex then proceeded to deal scornfully with the evidence of Vera, the house palour-maid. She was an utterly untrustworthy witness, a liar, schemer, and the mistress of Professor Appleby in his own home. Counsel hinted that her own conduct might, with advantage, be investigated by the police. Was she above suspicion—this woman who had tried to brand an innocent young wife with the mark of Cain?

‘Gentlemen of the jury, I do earnestly appeal to you to be guided by reason when you retire to consider your verdict. I do not ask for compassion for the prisoner. It is too late for that now. I do not ask you to consider her youth, her obvious helplessness and guilelessness, nor the life of suffering she has endured at the mercy of the deceased. I ask you—nay, I demand from you, twelve good men and true,’ said David Greatorex, thumping the table, ‘that you, selected for your intelligence and impartiality, who have patiently and attentively listened to the evidence in the case, do now swiftly and decisively reject the trumped-up evidence against this fair and innocent woman. I ask you to acquit her of this monstrous and iniquitous charge, so that she may leave the court a free woman and without a stain upon her character.’

And David Greatorex sat down, his face shining with his own belief and sincerity.

An astonishing and sensational thing happened then. The jurors were seen to whisper and confer amongst themselves, and then the foreman rose, and after signing and whispering to the clerk of the court, who conveyed a message to the judge, he faced his lordship, who sat gravely expectant, while a stillness of death fell upon the court.

The foreman spoke, emotion writ large upon his face, and his voice a little tremulous.

‘We, the jury, in this case of the Crown against Eleanor Appleby, do wish to stop this case, not desiring to hear any further evidence in the indictment for or against the accused.’

‘I understand,’ said his lordship gravely. ‘Then, gentlemen of the jury, you have already considered your verdict? And you are agreed upon it?’

‘We are,’ replied the foreman.

‘What say you? Guilty or not guilty?’

‘We find the prisoner not guilty,’ came the answer in an emotional voice, ‘and we wish to add a rider that we consider this indictment against Mrs Appleby should never have been brought.’

‘Not guilty!’

Cheers rang through the court. The tension was at last relaxed, and for a few moments most unseemly disorder reigned. Women wept openly, and men laughed and spoke to one another with delight. It was some moments before the ushers’ voices and the judge’s stern reprimand quelled the audible expression of the compassionate sympathy and gladness that flowed through the court at the verdict.

Then the judge spoke.

‘Eleanor Appleby, the jury, in conscientious discharge of their duty, have sought to end your suspense by respectfully begging that this trial shall be stopped. Without retiring to consider their verdict, they acquit you of the indictment against you. Their verdict of “not guilty” is one with which I entirely agree, and I am bound to say that I endorse their rider that the charge should never have been brought. You are therefore entitled to leave this court at once, a free woman, with honour untarnished and without a stain upon your character.’

And his lordship actually beamed upon her.

A minute afterwa

rds, however, he was compelled to give an order to clear the court, so great was the enthusiasm at the result. Even Alec Portal was unable to curb his joy and gladness. He rose from his seat and made his way to the well of the court, where he waved his hand to Eleanor delightedly.

She smiled wanly at him as she was led out of the dock by a motherly wardress. Never had she appeared so beautiful in his eyes. A tiny, hectic spot of colour stained the pallor of her cheeks as she looked at him, lashes tremulous, lips aquiver in that smile. She seemed to him a girl again—the spirit of girlhood incarnate. Yet a woman to love, to cherish and worship.

She was gone. But he would see her again outside the court. He would take her away to a land of sunshine and flowers. Their honeymoon, by gad! He laughed joyously at the thought. Where should they spend it? In Naples? In Rome? In the Mediterranean of sapphire-blue seas and skies? Or in sunny Havana, mecca of the millionaires, where the lofty, slender, smooth-skinned palms give a romantic grace to every skyline, where all is sweet music in that exotic, dreamy, curious island. Yes; there she might learn to forget.

Whilst he strode from the court, reckless and tingling with the consciousness of this great love that had come to him, another man stood staring into space. It was Derek Capel, unconsciously twirling that tiny moustache of his, yet with all the debonair, reckless charm eradicated from his face now. He looked haggard and worn; almost seedy. A policeman came along, and none too politely ushered the abstracted loiterer out of the court.

Derek went outside like a man in a dream. A spasm crossed his face, of mingled gladness and pain. She was free! Free! Thank Heaven for that. But—

Oh, he had seen the look she had given Alec Portal. Hopelessly, passionately in love himself, he was keenly intuitive in these matters. And he knew that his cause was lost.

Eleanor loved this other man. The thought drummed insistently in his brain. He had seen it in her shy smile, in the look she gave him even in that moment when the relief from the strain and suspense of months must have had an overwhelming effect on her. And he had dared to hope all this time, to think …

He stopped in the middle of the pavement. A surge of ungovernable, murderous passion shook his whole being. His handsome face was distorted, scarcely nice to look at.

‘Oh, blast!’ he said aloud, very bitterly.

So he wrestled with his demons as he trudged on with his hands in his overcoat pockets. He furiously repelled that insidious, murderous thought that had come to him … that awful thought in connection with Doctor Alec Portal.

No; the game had been played. He had lost. He must be an iconoclast—destroy the sweet image of the girl that was in his heart and brain. The only way to do that was to seek other distractions.

A newsboy came running at full tilt, crying his wares—that cry of ‘Piper! Late edishun!’ that is peculiar to London. He was doing a roaring trade. Derek Capel stopped and stared down the wet, shining pavements after him. The newsboy carried a bill bearing the words:

MRS APPLEBY: TRIAL VERDICT!

Derek Capel’s face worked strangely. Could he never get away from it all.

… All at once he saw the frosted glass of a public-house, and he went in, out of the drizzling rain.

And Alec? He waited at a side entrance of the Old Bailey from which he knew she would emerge, his clear-cut face very boyish and his eyes lit with that tender, exultant glow that comes seldom to a man. So he stood, tall and well groomed, pawing at the ground with his cane, while he gave his thoughts full rein. There seemed some magic in the air this chilly, wet November afternoon. His blood was turned to fire, consuming him. He was the eager, ardent lover—burning to see her.

He turned restlessly, oppressed by something, he knew not what. Was it this building of steel and stone that still seemed to hold her prisoner. Why did she not come? He would soon take her away from this chilly, foggy London in November.

Even then he did not see them; he was not properly sensible of them—those figures, grotesque, umbrella-clad, that thronged the opposite pavement, only held in leash by burly, impatient constables. They were the passers-by, the curious sightseers, the moving and component parts of London’s phantasmagoria—call them what you will. They throng to a hole dug in the ground by workmen; they press with morbid eagerness to the scene of an accident. Like weeds, they are not to be checked.

But Alec, with the eyes of a lover searching only for one object, did not see these monstrous shadowy figures that hung expectant under London’s growing pall of dusk.

Lighting-up time! She came out at last with the lights, whose glowing reflections danced on the wet pavements. A coat with silver-gray fur, like Columbine’s ruffles at neck and wrists, garbed her slimly. Alec jerked forward with London’s roar dying to sweet, subdued music in his ears. How pretty she was—how pretty!

‘Eleanor!’ Her name broke from his lips like a sob of happiness. ‘Oh, my dear … I thought you were never coming. I’ve been thinking awful thoughts—almost making up my mind to break in there and carry you away. But you are free! Free!’ He stopped suddenly, the wild song of gladness that had been welling in his heart dying—giving place to a queer dread.

For she was looking at him with those great, lovely eyes of hers, and they were haunted by fear unnameable.

She was looking past him wildly. She wanted to escape. And when he barred her path, perplexed and hurt, she covered her face with her little gloved hands and burst into tears.

He laid light hands on her arm. ‘Eleanor—look at me! Has anything happened?… Tell me, dear heart.’

But the next moment he knew, and inwardly he cursed them savagely as they broke the police cordon across the road and came rushing to see—those curious sightseers. Of course! He had forgotten that she was the beautiful Mrs Appleby, heroine of the latest and most sensational murder trial. He cursed himself as stark reality came back to him. He had been too precipitate. Stupid fool that he was—always blundering.

Girls pressed forward with autograph albums and pencils; there was the vivid flash that accompanies a camera exposure, and an untidy journalist working for one of the big London ‘dailies’ was endeavouring to persuade Eleanor to come to his office with him in a taxi, where a fat cheque awaited her in return for an exclusive interview with photographs.

Eleanor was frightened, pitiably frightened. Now she clung to Alec Portal, her little gloved hand plucking at one of the buttons of his coat, her eyes dewed with tears.

‘Oh, can’t you see?’ she gasped, ‘They’re staring! They’re all staring at me! Take me away from here—please, or I shall die of shame!’

Something like an oath was wrenched from his lips.

He glared at the eager throng that pressed around them, but for a moment he was oppressed by a sense of futility. All at once, however, he saw a big car, whose interior was lighted, and, desperate for the woman he loved, he raised his stick to signal to it. As if the driver anticipated his wishes, the long low car swung up to the kerb, and a man pushed open one of the doors hurriedly and jumped out on to the pavement, obviously holding the door wide for them and looking over towards them.

It was Chief Inspector Brent of Scotland Yard, his grizzled face somehow softened as he looked at the woman whom he had been chiefly instrumental in placing on trial for her life.

‘In here,’ he said, gruffly enough.

Alec Portal, with a surge of relief, piloted Eleanor towards the waiting motor-car, his hand on her elbow. Even at that moment, distracted as he was by the vulgar crowd, he knew a thrill that was akin to pain at the mere touch of her; her close proximity. A mad elixir seemed to run through his veins. Heavens, he loved her—loved her!

She was seated in the car and he beside her, and they were being whirled away.

Inspector Brent seemed to have foreknowledge of her intentions and wishes. He sat in a seat in front like a graven image, occasionally directing the uniformed driver; and the car swept on, through Euston’s broad thoroughfare, Tottenham Court Road, and towards

the great terminus of Paddington station.

Alec Portal had sat silent for some time, a feeling of unease growing on him. She seemed so defenceless, so alone in the world, that he yearned to take her in his arms, to tell her of his love.

And yet—there was some barrier between them; intangible, yet definite enough to chill his ardour. Scarcely was it the barrier of her shyness and reserve; so great was his love for her that he felt he might have surmounted that …

He turned restlessly.

He was almost afraid of himself, frightened of his own desires and thoughts and secret longings.

What a divine, sweet, intoxicating little thing she was. And she was free—free to become his wife! She must love him too, he thought fiercely. He could feel it—he knew it! They were made for each other.

She sat in the corner, her face half averted from him, stained with tears. He thought of some crushed, beautiful flower as he looked at her. And he longed savagely to take her in his arms. But then, like a cold douche, came remembrance of those hours of cross-examination, questioning, as she had stood in the dock under the pitiless gaze of the curious. The acid had been poured on her to test her. The cold white light of inquiry had flooded on her. It had served only to discover that she was innocent and pure.

Yet it must have seared her. She was afraid—trembling—utterly unnerved. Afraid to face the curious gaze of the world! He as a doctor should have known that. He lashed himself all at once with thoughts of his own callousness. What a brute—a callous brute he was—to impose his wooing upon her at this time!

Despite it all, as he stared at her he became unnerved, weak as any man might be.

‘Eleanor?’ he whispered huskily.

She turned to him with a start, mutely, her eyes questioning him in fear. And something he saw in the depths of those lovely brown eyes wrung at his heart. She was afraid of him too!

There was a barrier between them; a barrier, almost sinister, that had arisen out of the past.

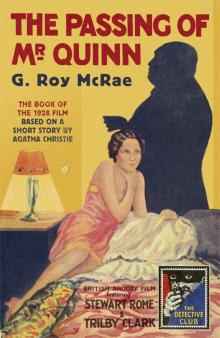

The Passing of Mr Quinn

The Passing of Mr Quinn